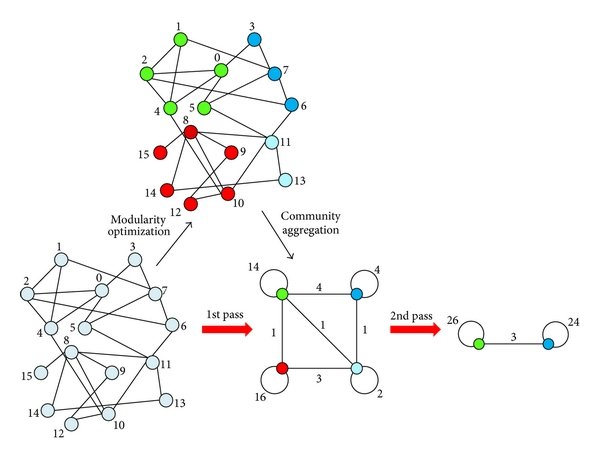

- I will illustrate the idea using the Louvain Method, one of the most widely used community detection algorithms.

- It optimises a quantity called modularity:

\[ \sum_{ij} (A_{ij} - \lambda P_{ij}) \delta(c_i,c_j) \]

\(A\) - The adjacency matrix

\(P_{ij}\) - The expected connection between \(i\) and \(j\).

\(\lambda\) - Resolution parameter

Can use lots of different forms for \(P_{ij}\) but the standard one is the so called configuration model:

\(P_{ij} = \frac{k_i k_j}{2m}\)

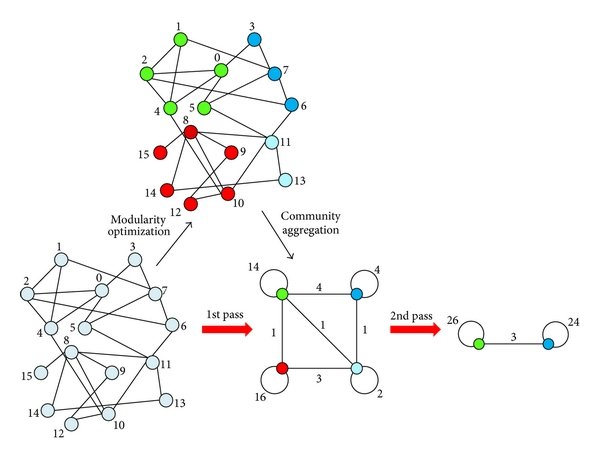

Loosely speaking, in an iterative process it

- You take a node and try to aggregate it to one of its neighbours.

- You choose the neighbour that maximizes a modularity function.

- Once you iterate through all the nodes, you will have merged few nodes together and formed some communities.

- This becomes the new input for the algorithm that will treat each community as a node and try to merge them together to create bigger communities.

- The algorithm stops when it’s not possible to improve modularity any more.

This is the original paper, for those interested in further reads:

- Blondel, Vincent D; Guillaume, Jean-Loup; Lambiotte, Renaud; Lefebvre, Etienne (9 October 2008). “Fast unfolding of communities in large networks”. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 2008 (10): P10008